Photo CSIRO: The scene in the control room. Click on the image to see more pictures in the control room.

The Landing:

On Monday 21 July 1969, at 6:17 a.m. (AEST), astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin landed their LM, Eagle, on the Sea of Tranquillity. The landing was an eventful one, in more ways than one.

The landing occurred during the coverage period of the Goldstone station. As the LM undocked from the command module to begin the descent, Armstrong reported, 'The Eagle has wings.' As the descent continued, the on-board guidance computer was being overloaded by information from both its landing and rendezvous radar. A series of alarms alerted Mission Control of the problem, and for a short time it appeared the landing might have to be aborted. The 64 metre dish at Goldstone was able to pull the very weak and variable LM signals out of the noise. The problem was diagnosed to be within safety limits, and the "go" to continue the landing was given. Had the 64 metre dish not been used, the mission would have been aborted at this stage since the neighbouring 26 metre dish at Goldstone had no usable signal at all.

Very soon, however, it was evident to Armstrong that the guidance system was not performing as expected. Landmarks were appearing about 2 seconds ahead of schedule, indicating that the LM was overshooting its planned landing spot. Mission rules dictated that if the error reached 4 seconds, then the landing would have to be aborted, since it would have brought them down in a very rugged part of the Moon. Apparently, mascons, or areas of mass concentration, were gravitationally pulling the Eagle ahead of the planned landing site.

As the Eagle approached the surface, Armstrong could see that it was heading straight for a large crater (West Crater), surrounded by a large boulder field - a crash seemed inevitable. He immediately took over manual control of the landing, and stopped the descent of the LM while continuing the forward motion. With fuel running dangerously low, he desperately searched for a safe landing place to bring the LM down. Finally, with less than 50 seconds of fuel remaining, the Eagle touched down. With his heart pounding at 150 beats per minute, Armstrong then uttered the now famous words; "Houston, Tranquillity base here, the Eagle has landed". Mission Control erupted with joy; the tension of the last few minutes suddenly released. The Eagle had landed some 6.5 km (4 miles) down range from the planned landing site at lunar coordinates 0o 41' 15" N and 23o 26' E - close to the terminator of the 6 day old Moon.

Click hear to hear the landing WAV file (1.2 MB) or MP3 file (455 KB).

Preparing for the EVA:

After landing, the LM was checked out and the "go" was given to remain on the surface. The flight plan originally had the astronauts sleeping for six hours before preparing to exit the LM. It was thought that following a rest, the astronauts would be refreshed and would have had enough time to adapt to the 1/6th gravity. About ten hours after landing, at 4:21 pm (AEST), the EVA would have commenced. At that time the Moon would have set at Goldstone twenty minutes earlier, at 3:57 pm (AEST). Parkes would have been the only large antenna tracking the LM, and thus been the prime tracking station for the reception of the moonwalk TV - with the Moon high in the sky, having risen above the telescope's horizon at 1:02 pm (AEST).

Photo CSIRO: The scene in the control room. Click on the image to see more pictures in the control room. |

As the hours passed, it became evident that the process of donning the portable life support systems, or backpacks, the lunar boots, gloves, etc. took much more time than anticipated. The astronauts were being deliberately careful in their preparations. Furthermore, they experienced some difficulty in depressurising the cabin of the LM. The air pressure in the cabin took much longer to drop than expected. The hatch could not be opened until the pressure in the cabin was below a certain level since the pressure inside tended to prevent the hatch from opening easily - the astronauts didn't want to risk damaging the thin metal door by tugging on it.

Photo David Cooke: Dave's blurred image of the famous wind storm on the Parkes horizon. This is the only known photograph of the storm ever taken. |

The weather at Parkes on the day of the landing was miserable. It was a typical July winter's day - grey overcast skies with rain and high winds. During the flight to the Moon and the days in lunar orbit, the weather at Parkes had been perfect, but today, of all days, a violent squall hit the telescope (Bolton 1973). Present in the control room were the NASA personnel, John Bolton, Dr Taffy Bowen, the PMG senior technical officer, Brian Coote, and Neil 'Fox' Mason, who was the driver given the responsibility to operate the dish at this historic moment. Seated next to Fox was Denis Gill, the technician responsible for the control desk. Also present was an assortment of other CSIRO staff. They included Harry Minnet, John Shimmins, Dave Cooke, and Jasper Wall. Other staff members were present downstairs in the tea room and on the azimuth track, ready to swing into action if anything untoward should happen. According to Jasper:

Receiving the TV pictures:

The giant dish of the Parkes Radio Telescope was fully tipped over to its zenith axis limit, waiting for the Moon to rise and ready to receive the television pictures once the TV circuit breakers in the LM were pushed in. John Bolton realised that the TV would begin during the ten-minute coverage period of the off-axis receiver. By turning a dial on the control desk, he turned the feed rotator and positioned the off-axis receiver so that it lay directly above the main, on-focus, receiver. This gave it its maximum field-of-view below the main beam.

As the moment approached, dust was seen racing across the country from the south. The giant dish, being fully tipped over, was at its most vulnerable. Two sharp gusts of wind exceeding 110 kph (70 mph) struck the dish, slamming it back against the zenith angle drive pinions, and causing the gears to change face. The telescope was subjected to wind forces ten times stronger that it was considered safe to withstand. The control tower shuddered and swayed perceptively from this battering, creating concern in all present. John Bolton rushed to check the strain gauges around the walls of the control room. The atmosphere in the control room was tense, with the wind alarm ringing and the telescope ominously rumbling overhead. Fortunately, cool heads prevailed and as the winds abated the Moon rose into the off-axis beam of the telescope just as Aldrin activated the TV at 12:54:00 p.m. (AEST).

Click on image to see an animated GIF of the tracking process. |

Once the off-axis beam was level with the main, on focus, beam, the telescope was moved quickly in azimuth to lock onto the radio source and track it in the main beam of the telescope. This, then was the procedure employed to receive the pictures of Armstrong's first step on another world, by the Parkes Radio Telescope.

Japser Wall recalls:

John Bolton was a pioneer of radio astronomy, and an expert in optically identifying radio sources in the sky. His success in acquiring the Apollo 11 TV signal in very trying conditions, even before the source had risen in the main beam of the telescope, was surely one of the most breathtaking examples of his expertise in action. Click here to hear John Bolton describe the event - WAV file (41 MB) or MP3 file (372 KB).

Years later, John Bolton would insist that he had acquired the signal simultaneously with the Goldstone and Honeysuckle Creek stations. At the time, he was engrossed with the process of tracking the source in the off-axis beam. Only after it was acquired in the main beam did he relax and view the pictures being received at Parkes on the 10-inch SSTV monitor, located at the far end of the control room. Robert Taylor, who had been monitoring the TV pictures from the outset, assured John that the TV was acquired just as Aldrin pushed in the TV circuit breaker. He also viewed the replay of the telescope's master tape, and saw no difference with it and the ABC version replayed later that evening. Indeed, a small television set in the control room allowed the staff to view the relayed signal via the live-to-air ABC broadcast.

Photo CSIRO: Fox Mason at the control desk. This photo was taken in 1970. |

"I was disappointed, but I had an important job to do. Besides, I had to be on my best behaviour because all the bosses were there looking over my shoulder!"

The weather remained bad at Parkes, with the telescope operating well outside safety limits for the entire duration of the moonwalk.

The EVA lasted a total of 2 hours 31 minutes and 40 seconds, hatch open to hatch closed. The telescope continued tracking the LM and receiving TV pictures from the camera until it was shut off by the astronauts about 1/2 an hour after the end of the EVA. The tracking continued at Parkes until 6:17 p.m. (AEST).

Photo NASA: The gathering storm over Parkes as viewed from Lunar Orbit on 20 July 1969 (AEST). Australia is clearly visible with the storm clouds over the south-east of the country. The photograph was taken by Michael Collins, the Command Module Pilot, on the day before the lunar landing. Click here to see the storm patterns during the EVA. |

He took a photograph of the dish, with the passing storm clearly visible on the horizon. It had been a dramatic day!

Armstrong's first step on another world:

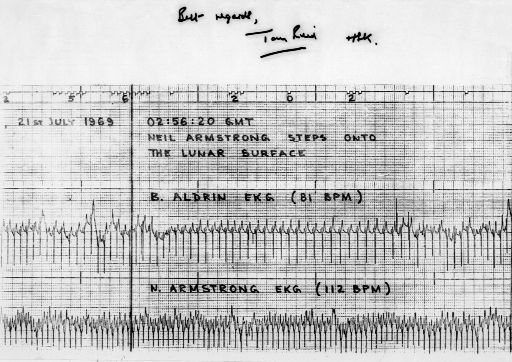

Armstrong gingerly stepped onto the Moon at 12:56:20 (AEST). His heart rate was being monitored, along with other biomedical data, at Honeysuckle Creek. The Parkes and Honeysuckle Creek signals were synchronised and blocked. A recording was made of Armstrong's heart rate. As can be seen in the figure below, it peaked at 112 beats per minute (bpm) as he stepped onto the Moon. He was obviously nervous, and this may account for why he forgot to include the article, 'a', when he uttered his now famous words:

Contrary to popular belief, he wasn't instructed by NASA on what he would say at that point. Armstrong later recounted that he hadn't thought about it until after he had landed (there wasn't any point if the landing failed), and that he hadn't decided on the final form of his words until he was on the porch of the LM, beginning his descent. Apparently, he had the thought of saying something along the lines of the well-known children's game "baby steps, giant steps".

Photo CSIRO: Armstrong's heart rate as he stepped onto the Moon. This was recorded at Honeysuckle Creek and sent to Parkes. It was signed by Tom Reid the Honeysuckle Creek station director, and the annotation is by Ed von Renouard. |